How Can We Get More Animals Adopted

Abstract

A considerable number of adopted animals are returned to animal shelters post-adoption which can be stressful for both the creature and the owner. In this retrospective analysis of 23,932 animal records from a US shelter, we identified animal characteristics associated with the likelihood of return, key return reasons, and outcomes post-return for dogs and cats. Binary logistic regression models were used to describe the likelihood of return, return reason and outcome based on intake age, intake blazon, sex, breed and return frequency. Behavioral issues and incompatibility with existing pets were the about common render reasons. Age and breed grouping (dogs only) predicted the likelihood of return, return reason and post-adoption render outcome. Adult dogs had the greatest odds of post-adoption return (OR 3.40, 95% CI ii.88–4.01) and mail service-return euthanasia (OR 3.94, 95% CI two.04–7.59). Toy and terrier breeds were 65% and 35% less likely to be returned compared with herding breeds. Pit bull-blazon breeds were more than probable to exist returned multiple times (X ii = 18.11, p = 0.01) and euthanized post-render (OR 2.threescore, 95% CI 1.47–4.61). Our findings highlight the importance of beast behavior in the memory of newly adopted animals and provide useful direction for allocation of resources and future adoption counselling and post-adoption support services.

Introduction

An estimated 3.two 1000000 animals are adopted from animal shelters in the US each year1, and the rate of adoption appears to be increasingii. About owners study high levels of satisfaction with their newly adopted petthree,4,v, however a considerable number of adopted animals are returned to shelters for various reasons. Current estimates range between 7 and twenty%6,seven,8,9,10,11,12. Over recent years, the perception of returned adoptions within the sheltering community has begun to modify13, 14. While returns were once viewed equally "failed" adoptions, there is at present more emphasis placed on the possible benefits of temporary adoptionsfifteen, such every bit brusque-term stress relief15 and an increased understanding of the animals' behavior in the abode surroundings. Withal, the return process can exist stressful for both the animal and the owner. The animal'due south likelihood of a alive release effect (leaving the shelter alive) may exist jeopardized if the shelter does not have the required infinite or resources available, meaning the animal may be euthanized (humane killing of the creature). Re-entry to the shelter also means the animal is over again exposed to the multitude of stressors associated with the shelter environs (see Taylor and Mills16 for review). Shore17 reported more than than one-half of relinquishing adopters plant the render process 'very difficult' and 41% indicated they would non prefer some other beast in the future17.

Behavioral bug are reported as a cardinal reason for unsuccessful dog adoptions worldwidesix, 8, 17, 18. A recent study of 102 returned dogs at a shelter in Texas found 56% of dogs were returned due to behavioral issues, 31% were returned for owner-related reasons and 9% were returned for medical needs. Aggression towards humans and animals were listed as the 2 most common return reasons18. In the UK, 59% of dogs returned to Dogs Trust shelters occurred due to behavioral bug, with dogs displaying aggression towards people having the highest likelihood of return8. Mondelli, et al.7 found 39% of returns to a shelter in Italy were attributed to misbehavior, such as barking, destruction and hyperactivity, and a further 15% were returned for aggression. At a shelter in Northern Ireland, Wells and Hepper9 found a significantly higher proportion of returned dogs exhibited behavior problems compared with retained dogsnine.

The primary factors that drive cat returns are less clear cut5, 18, 19. Hawes, et al.xviii establish that cats were returned more ofttimes due to owner-related reasons than fauna-based reasons, such equally moving, inability to afford basic care and medical needs of the adopter. However, when considering the return reasons individually, assailment towards humans and destructive tendencies were ranked as the second and equal third most common reasonseighteen. Other studies have reported behavior as the most prevalent return reason, although allergies to the cat and owner circumstances also led to a number of unsuccessful adoptions5, 19. Information regarding postadoption returns of other species are scarce.

The likelihood of mail-adoption returns is too associated with a range of owner and brute characteristics. The presence of children in the adopted home has been linked with a college risk of return5, 8, 10, 20. Immature owners and first-time owners likewise comprise a higher proportion of returned adoptionsx, xx. The risk of render is greater among older animals5, nineteen, male dogs and medium to big dogs7, viii. Conversely, caretaking behaviors of owners, such as visiting a veterinarian20, 21, allowing the fauna to slumber in a family unit member's bed and attending grooming classes, take been associated with a decreased risk of return8. Despite the influence of animal and owner variables on the risk of render, there is a lack of data regarding differences in return reasons based on animal or possessor characteristics.

There is as well a dearth of information about animals' outcomes mail-return. 2 previous studies have found that returned dogs had a euthanasia rate betwixt 40 and 50%, although both studies were conducted more than a decade ago12, 22. Recent research reported drastically unlike results with 791 of 816 returned dogs (97%) having a alive release consequence. In this report, returned dogs had 4.77 times greater odds of live release compared with owner surrenders. This figure may overestimate the true live release rate of returned dogs equally the authors considered adoption, transfer to rescue group, and sent to foster care as a live release outcome. Including the latter every bit an event is inconsistent with their definition of foster intendance equally an interim home for rehabilitation prior to permanent adoption11.

Understanding the central factors that outcome in unsuccessful adoptions across all species will enable animal shelters to develop preventive strategies and target their resource towards the animals and owners who need them most. The aims of this study were to: (a) identify characteristics associated with a greater adventure of return; (b) describe the key render reasons and the variations in return reasons by fauna characteristics; and (c) examine animals' outcomes postal service-render and place factors that predicted euthanasia.

Results

Between 2015 and 2019, 23,932 animals were adopted from Charleston Animal Society, including 9996 dogs, xiii,450 cats and 486 animals of other species. Of the adopted animals, 9.2% (n = 2211) were returned to the animal shelter within six-months of adoption. Dogs were the near ofttimes returned species with a return rate of 16.iii% (n = 1628), followed by rabbits at 9.0% (n = 15). Cats were returned at a significantly lower rate of 4.2% (n = 559, 10 2 = 997.64, p < 0.001). The remainder of returns consisted of two pigs, four guinea pigs, two mice and one hamster. Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of all animals adopted betwixt 2015 and 2019.

Of the animals returned to the shelter, most were returned once (85.7%, n = 1895), 11.2% of animals were returned twice (n = 220 dogs, n = 28 cats) and 2.0% of animals were returned three times (n = 44 dogs, northward = 6 cats). Xiv dogs were returned four times, 3 dogs were returned 5 times and one dog was returned six times. Dogs who were returned in one case did not differ in sex activity (X ii = 2.32, p = 0.13) or render reason (X two = 8.10, p = 0.62) from dogs who were returned more than once. Intake age was associated with multiple return status (10 2 = 14.94, p = 0.002) with significantly fewer puppies and more young developed dogs returned more than than once. Brood groups also differed between one-off returns and multiple returns (10 2 = 18.11, p = 0.01) with multiple-returns comprising more pit bull-type breeds and fewer sporting breeds. For cats, in that location were no pregnant differences between animals that were returned once and multiple returns. Overall, there was poor understanding between the get-go and 2d returning owners in terms of the reason provided for return (κ = 0.08, 95% CI 0.03–0.13, p = 0.002). The strongest understanding was seen between owners who returned animals due to the animal'due south health (κ = 0.29, 95% CI 0.eighteen–0.twoscore, p < 0.001), although the strength of understanding was only considered 'fair'.

Associations betwixt animal characteristics and likelihood of return

The likelihood of return was associated with intake age and breed grouping for dogs, and intake age for cats (Table ii). Adult dogs (> two–8 years) had the highest likelihood of return, with an odds ratio of three.40 (95% CI 2.88–four.01), followed by young adults and senior dogs who had an odds ratio of 2.90 (95% CI 2.47–iii.41) and two.24 (95% CI 1.64–3.06), respectively. For cats, senior cats had the greatest likelihood of return compared with kittens (OR four.97, 95% CI 3.34–vii.forty), followed by adult cats (OR iv.10, 95% CI three.27–5.13) and young adult cats (OR 3.02, 95% CI ii.39–3.fourscore) and. Considering brood, dogs in the toy brood group were 65% less probable to exist returned following adoption compared with herding breeds (OR 0.35, 95% 0.26–0.47) and terriers were 35% less likely to exist returned compared with herding breeds (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.49–0.86). Intake type was not associated with the likelihood of return for dogs or cats.

Return reasons

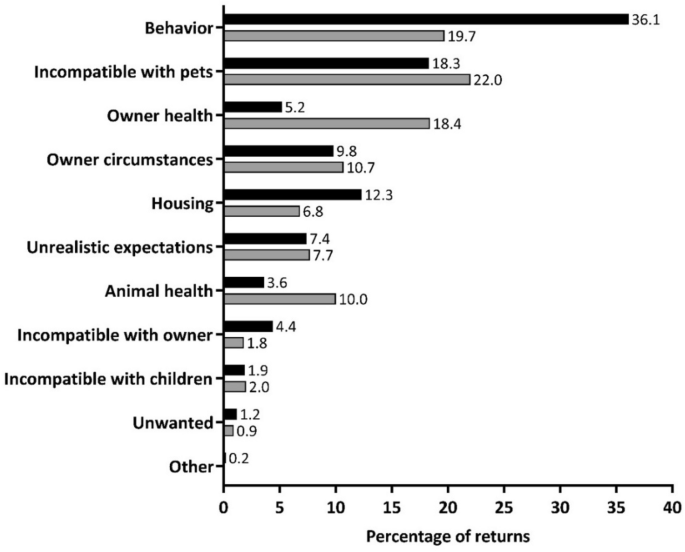

The return reasons for dogs and cats are presented in Fig. 1 and Tabular array 3. Behavioral issues (36.1%) were the most mutual reason for return for dogs, followed past incompatibility with existing pets (eighteen.3%). For cats, the most common return reason was incompatibility with existing pets (22.0%), followed by behavioral issues (19.vii%) and owner's health, including allergies (18.4%). Rabbits were mainly returned due to behavioral issues (n = four, 26.7%), incompatibility with existing pets (due north = 3, 20.0%) and housing issues (due north = 3, 20.0%). All guinea pigs were returned due to incompatibility with pets (n = 4). The 2 pigs were returned due to behavior and incompatibility with pets, the mice were returned due to being unwanted (n = 2) and the hamster was returned due to unrealistic expectations.

Categorized reasons for returns, including the start return for animals that were returned multiple times. Black confined represent dogs (north = 1627) and grey bars represent cats (northward = 559).

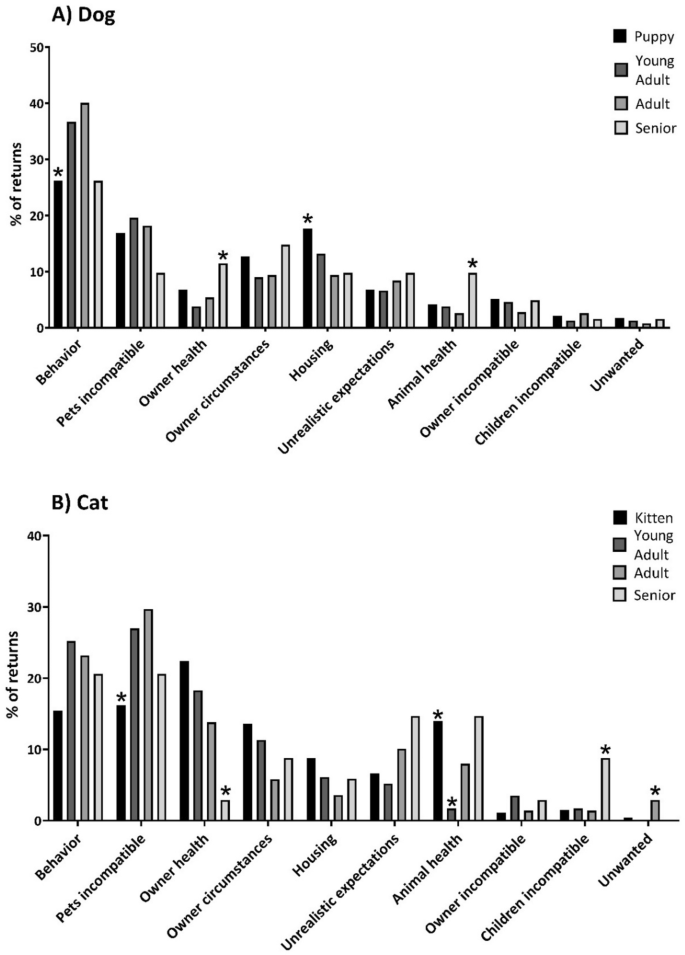

Return reasons differed across historic period groups for both dogs (X 2 = 57.96, p = 0.002) and cats (X two = 69.91, p < 0.001) equally shown in Fig. 2. Breed groups were associated with return reasons for dogs (X ii = 99.72, p = 0.01). Hounds were returned more than often than other brood groups due to the owner'southward health or possessor circumstances, while toy breeds were returned more oft for the animal's health and incompatibility with children. Sporting breeds were more often 'unwanted'. Sex was not significantly associated with return reasons for dogs (X 2 = 4.58, p = 0.92) or cats (10 ii = eleven.32, p = 0.26).

Categorized render reasons by age grouping. *Denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05).

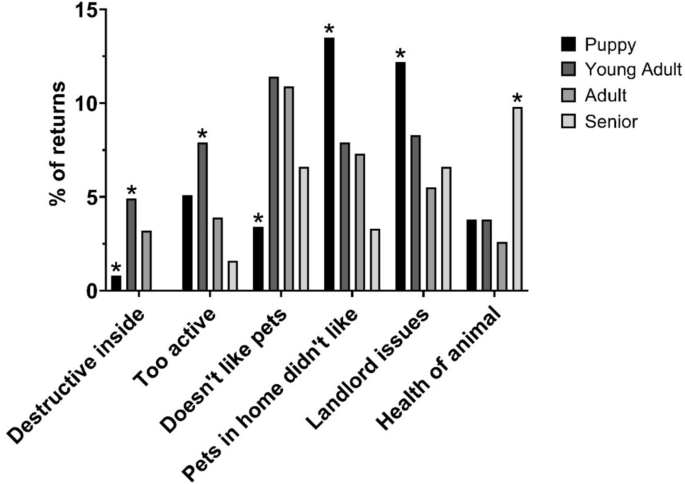

Canine return reasons were analyzed individually if more than than 50 owners provided the return reason, which showed age at intake was significantly associated with the following reasons: destructive inside, too active, doesn't similar pets, pets in home didn't similar, landlord problems and health of animal (Table 4). The differences in return reasons based on age are shown in Fig. 3. Breed group was associated with 'aggression to animals' in dogs with significantly more working breeds and fewer terrier breeds returned for aggression to animals.

Differences in non-categorized return reasons for dogs based on age group. *Denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Logistic regression models including return reason as a dichotomous variable (owner or animate being-based) mirrored the results of the Chi-Square analysis, highlighting a significant association betwixt return reason and historic period at intake for both dogs and cats, and breed for dogs simply (Table 2).

Result following return

Most returned animals were re-adopted (Table i), including fourscore.3% of dogs and 90.2% of cats. Outcome was associated with intake age, breed group, sex, render reason and render frequency for dogs (Table 2). Render reason was the strongest predictor of euthanasia followed past historic period.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest to appointment to investigate post-adoption returns in a sample of 23,932 adopted animals with a ix.ii% return rate. Dogs were the most frequently returned species with a return charge per unit of sixteen.iii%. Cats had a lower return rate of four.ii% and almost 1 in ten rabbits were returned post-adoption. Of those returned, most animals were returned one time during the study period although 14.3% of returned animals were returned more than once. Age at intake and breed (dogs only) predicted the odds of return, return reasons and post-return outcome.

The likelihood of return increased significantly for both dogs and cats over the historic period of 6 months. Adult dogs were over three times more likely to be returned, followed by young adults and senior dogs who had 2.nine and 2.two times the odds of existence returned compared with puppies. The elevated risk of return in adult dogs may exist explained past differences in behavior based on age of acquisition. Research has shown that as the age at acquisition increases, and so too does the risk of resources guarding23, and destructive behaviors24. Even so, in both studies other variables had a greater influence on the likelihood of behavioral problems, such as the dog's sex24 and owner's beliefs23. Variations in early on life feel may too produce behavioral differences and therefore, influence the likelihood of return25. The lower odds of return among senior dogs may be attributed to reduced practice and grooming requirements, particularly if the domestic dog has lived in a abode previously. This finding is somewhat at odds with previous reports that older animals may be at greater risk of relinquishment due to ill-health26 which speaks to the possible differences between the experience of a returned adoption and an owner relinquishment. Interestingly, young developed dogs comprised a college proportion of multiple-returns than the other historic period groups, perhaps reflecting an adolescent phase characterized by increased conflict beliefs27. Qualitative research in the field has documented a similar tendency. Shore17 found some returning owners indicated they would adopt a canis familiaris of a different age in the future, although the direction of modify was split up. Several respondents were interested in acquiring an older canis familiaris, while others would larn a puppy. Ane respondent said she would prefer either a very immature dog or an older canis familiaris in the time to come just would avoid dogs in between17. For cats, the risk of return increased considerably for each age grouping. Young adult cats, adult cats and senior cats were 3.0, four.ane and v.0 times more likely to exist returned than kittens, respectively. The willingness of cats to interact with humans has been shown to decrease with historic period which may hinder the development of the homo-cat bond and increase the risk of return28. Kittens are also more adaptable to novel environments29.

Brood group influenced the likelihood of return for dogs in that toy and terrier breeds were significantly less likely to be returned. The association between breed group and risk of return may be attributable to the domestic dog's size as previous research has shown medium and big dogs are more likely to be returned than small dogs8. We could not test this hypothesis due to a lack of data regarding dogs' weight. Breed group was also associated with the frequency of return with pit bull-type breeds comprising a higher proportion of multiple-returns than other brood groups.

Behavioral issues were a primal reason for render of both dogs and cats, which parallels the electric current torso of evidence and affirms the importance of creature beliefs in the development of a positive man-beast relationship8, 9, 12, 18. Charleston Animal Society provides a multitude of behavioral back up services for adopters, although data regarding the utilization of these services was non available. Contempo reports indicate relatively few owners accept behavioral back up18, 30. At a shelter in Texas, less than one-half of returning owners utilized behavior support services, with 18% of dog adopters and seven% of cat adopters contacting the beliefs team more than once prior to returning their pet18. Future studies on the use and efficacy of postadoption behavioral support programs in reducing returns would be of great value to the field. Incompatibility with existing pets contributed to approximately 20% of cat and domestic dog returns; a higher charge per unit than previous reports which ranged between 317 and 19%5. Our findings emphasize the importance of considering existing pets during adoption counselling. Cat adopters with existing pets may besides do good from adopting a kitten rather than an older cat as kittens had a significantly lower rate of return due to incompatibility with existing pets. The ideal historic period grouping for dog adopters with existing pets is more circuitous as puppies were returned at a lower charge per unit for 'doesn't like pets' just a college rate for 'pet in the habitation didn't like'. Allergies were also a meaning commuter of returns for cats, contributing xv% of all true cat returns which is broadly comparable to previous studies5, 17, xix.

Age at intake was associated with return reasons for both dogs and cats. Considering owner- and animal-related render reasons as a dichotomous variable, nosotros institute young adult and adult dogs were more likely to be returned for animal-related reasons than puppies. Specifically, puppies were returned at a lower rate for behavior issues, namely 'destructive inside', while immature adult dogs were returned more than frequently for 'destructive inside' and 'besides agile'. Once more, the increased charge per unit of behavioral returns among young adults could be attributed to a phase of adolescent behavior27. Adopters' expectations for ownership may also vary betwixt age groups. Most prospective dog owners expect some difficulties with canis familiaris training and beliefs31, although puppy adopters may anticipate more 'puppy-similar' behavior, such as destructive tendencies32. On the reverse, puppies were returned at a higher rate for housing problems, namely 'landlord issues'. Perhaps, puppy adopters encountered more house-grooming issues that led to post-adoption returns. It is also possible that puppy adopters were more likely to impulsively adopt without approving from their landlord, but farther research is needed to confirm this hypothesis. We also found senior dogs were returned at a college rate due to the health of the owner or beast. Older adults may be more inclined to adopt senior dogs due to their perceived lower grooming and do needs, although further research is needed to support this hypothesis. Amidst cats, we found adult and senior cats had an increased likelihood of return due to animal-related reasons. As described higher up, this may be related to the reduction in sociality with increasing historic period28. Further analyses of the categorized return reasons showed a higher proportion of kitten returns occurred due to health concerns, possibly upper respiratory infections (URI). URIs are mutual in the shelter environment and affect kittens at a college rate due to their increased susceptibility33, 34. Senior cats were returned at a higher rate for incompatibility with children which is conceivable every bit older cats are reported to accept the to the lowest degree satisfactory kid-true cat relationships35.

Return reasons also differed based on breed group in dogs. Sporting breeds and hounds were less likely to be returned for animal-based reasons than herding breeds, with hounds returned at a college rate due to the owner's wellness and circumstances, and sporting breeds returned at a higher rate for being unwanted. The categorization of return reasons too showed toy breeds were returned more frequently due to the animal'south health and incompatibility with children. Because the individual return reasons, working breed dogs were returned at a college rate for aggression to animals which is unsurprising given one of the historical roles of the breed group is guarding36. Hereafter, prospective inquiry focused on the influence of canis familiaris breed on return reasons would enhance our understanding of these associations.

Most returned animals were re-adopted, including fourscore% of dogs and 90% of cats. The likelihood of re-adoption was associated with intake age, return reason, return frequency and sex for dogs. Age was a stiff predictor of euthanasia with adult and senior dogs having approximately four times greater odds of euthanasia, and young adult dogs displaying 2 times greater odds of euthanasia compared with puppies. Render reason was also a meaning predictor of euthanasia for dogs. Dogs who were returned for animate being-related reasons were more than four times more probable to be euthanized than dogs returned for owner-related factors. Older animals and those returned for animal-related reasons may accept had behavioral and/or medical concerns that meant they were unsuitable for rehoming. Animal behavior and health are as well important considerations for adopters when choosing an animal37, 38 and animals relinquished for behavioral bug, onetime age, illness, and injury are less likely to be adopted39. Canis familiaris breed was also associated with issue. Pit bull-blazon breeds were more two and half times more than likely to be euthanized post-return than other breed groups, replicating the findings of previous enquiry39,xl,41. The procedure of breed designation is undoubtedly subject field to potential error. Shelter staff are inconsistent in their breed designations, and significant differences take been plant between shelter brood labels and DNA assay42,43,44. Irrespective of the accurateness of designated breeds, breed labels have been identified as an of import attribute in adoptability40, 45. Dogs labelled as pit bulls have been shown to spend longer in the shelter compared with phenotypically similar dogs labelled equally culling breeds. In the same study, participants rated pit bulls every bit less intelligent, less approachable, less friendly, less adoptable, and more aggressive than Edge Collies and Labrador Retrievers40. Pit bull-blazon breeds may also differ behaviorally from other breeds, although current data is mixed. Some inquiry suggests pit bulls show higher levels of interdog aggression46, hyperactivity, impulsivity and compulsive behavior47 while other studies accept constitute the beliefs of pit bulls was no worse than other breeds48, 49. Although it is unclear whether the association between pit balderdash-blazon breeds and euthanasia post-return is attributable to the brood-specific characteristics of the domestic dog or the perceptions of the dog based on breed label, futurity adoption counselling and post-adoption support services could target this group of at-risk dogs to potentially reduce returns and mail service-render euthanasia rates. Shelters may also see differences in mail service-return outcomes with removal of the breed label. Male person dogs and dogs who were returned more than in one case also had slightly elevated odds of euthanasia.

One limitation of this study is the reliance on possessor reports of return reasons. Owners may provide unreliable information at the time of return due to social desirability bias, in which individuals give answers that they believe will exist viewed more favorably by others, or to reduce the animal's take a chance of euthanasia. Enquiry on the topic has produced mixed results. Some data indicates that relinquishing owners reliably report their dog'southward behavior at the time of relinquishmentfifty while other studies accept found inconsistencies between relinquishing possessor reports and domestic dog beliefs51, 52. Owner-reported return reasons are likely to too be influenced past the adopter'south expectations for buying, ownership behaviors, perception of creature behavior and tolerance of behavioral problemsviii, 21. For example, animal behavior that is construed as normal by one adopter could be considered problematic past another53. This miracle has been documented previously whereby some owners do non report behaviors as a problem despite reporting occurrences of the behavior itself. Enquiry has constitute dog owners who are employed/students, utilise positive reinforcement preparation methods only, do not attend puppy classes or own small dogs are less likely to report problem behaviors as a problem54. The multifactorial nature of returns means the categorization of return reasons is also subject to potential error. For case, a canis familiaris that is returned for being 'besides active' may accept arousal and hyperactivity issues that make it difficult for the owner to manage safely, or the dog's action level may simply exist incompatible with the owner's lifestyle. Due to the retrospective nature of the written report, we were unable to decipher such ambiguities. Future, prospective enquiry should aim to disentangle the owner- and animal-related factors that contribute to post-adoption returns to increase our understanding of render reasons. The retrospective study pattern as well prevented the inclusion of additional variables, such every bit animal behavior, size, buying behaviors, and possessor-animal attachment, that probable influence the human–canis familiaris relationship and the gamble of render49. In particular, dog size may affect the likelihood of returnviii and could be confounding the results surrounding brood. Charleston Animal Guild operates an open adoption policy and encourages adopters to return animals direct to the shelter if necessary, although information technology is possible that we misclassified animals who were rehomed through other avenues. The uncertain history of many animals inbound the shelter meant some variables were discipline to potential error. To reduce the risk of misclassification, we used categorical groupings where appropriate. Finally, despite the large sample size of the report, the generalizability of the findings is limited every bit the data were collected from a single facility that likely differs from other shelters. Charleston Animal Society provides post-adoption back up services which may have reduced render rates by helping new owners to manage behavioral or medical difficulties. On the other hand, the open up return policy could have increased return rates as owners were aware that they could return the beast without any ramifications.

Through this study, we accept identified groups of the shelter population that feel greater chance of post-adoption return. These data are crucial to promote successful adoptions and better animals' outcomes as they highlight opportunities for targeted interventions and assist in the early recognition of adopter-animal mismatches. Our results also pave the way for future inquiry focused on the usefulness of interventions, such as behavioral support services, in reducing returns.

Conclusion

The well-nigh common reasons for returned adoptions at this big animal shelter in South Carolina were behavioral issues and incompatibility with existing pets. Taken together, our findings indicate that adult (> two–viii years) and young developed dogs (6 months-2 years) were most probable to be returned post-obit adoption, primarily due to fauna-based reasons, such equally behavior. Developed dogs had the greatest odds of euthanasia post-return at most iv times that of puppies. Toy and terrier dogs were less likely to exist returned, while pit balderdash-type breeds were more probable to be returned multiple times and more likely to exist euthanized mail service-return. Our study adds to a growing body of testify that highlights the importance of beast behavior in the retention of newly adopted animals and the development of the man-creature relationship. Our findings also provide useful direction for future adoption counselling and allotment of resources, including post-adoption support services.

Methods

Creature shelter characteristics

Charleston Beast Society is a large, open admission shelter located in South Carolina, U.s.a.. The shelter is the just open access shelter in the region and took in approximately 3500 dogs and 4700 cats per year between 2015 and 2019. Most animals that entered the shelter were strays, including 72% of dog and 89% of true cat intakes. The residue of shelter intakes were generally owner relinquishments, including 24% of dog and 10% of cat intakes. Charleston Animal Gild operates an open adoption policy meaning adopters can adopt and return animals to the shelter without judgement or ramifications. If the animal is returned inside 30 days of adoption, adopters receive a refund in the form of a voucher for future adoptions (except for animals adopted during fee-waived promotions). The shelter as well provides mail service-adoption behavioral and veterinarian support services. All adopted animals are eligible for a free veterinary bank check-up at local veterinary clinics and adopters can seek behavioral advice from the shelter's behavior team if needed. In most cases, adopters of animals with identified behavior problems also receive postal service-adoption follow-up phone calls from the beliefs team.

Variables

For all animals adopted betwixt 1st January 2015 and 31st December 2019, sex activity, known or estimated date of birth, brood (dogs only), intake date, intake blazon and adoption date were extracted from the electronic shelter records (PetPoint Data Management Organization, Version 5, Pethealth Software Solutions Inc., USA). Charleston Animal Society consented to the sharing of data every bit the data are not publicly bachelor. Animals returned to the shelter within 30 days of adoption were classified as a 'return' in the shelter'due south electronic database. To capture animals returned exterior of the 30-twenty-four hours window, we extracted data for animals relinquished to the shelter inside six months of the adoption where the person'southward ID was the same between the adopter and the relinquishing owner. We then extracted return/relinquishment reason, return/relinquishment engagement, render/relinquishment outcome date, and return/relinquishment outcome (adoption, euthanasia, return to owner/guardian, transferred to some other fauna shelter, died, return to field).

Length of stay was calculated equally the number of days betwixt the animal's intake engagement and event date, including any fourth dimension spent in a foster dwelling. Age at intake was calculated as the number of months between the animal's recorded date of nascence and start intake date. For returned animals, historic period at intake was calculated equally the number of months between date of nascence and engagement of initial intake (prior to the first return between 2015 and 2019). Mail-return intake age was calculated as the number of months betwixt the brute's date of nascence and render date. Intake historic period was then categorized as puppy/kitten (< 6 months), young adult (> 6 months–2 years), adult (> 2–8 years) and senior (> 8 years). Primary breed was adamant at intake based on staff opinion due to the canis familiaris'due south phenotypic characteristics or the breed provided by the relinquishing owner. Staff could include a secondary breed in the electronic record or select 'mix' to bespeak the dog was a mixed breed. Dogs were so categorized based on their primary brood designation in accordance with the American Kennel Club's breed groups as herding, hound, non-sporting, sporting, terrier, toy and working55, with one additional category for pit bull-blazon breeds40. Dogs listed as Catahoula Leopard dog and Treeing Tennessee Brindle were coded as hounds56. The total list of breeds and breed groups are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Spay/neuter status was not included in the analyses as the fauna shelter mandates that all animals are sterilized prior to adoption.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for intake age group, brood group (dogs merely), intake blazon, length of stay and outcome type. Length of stay was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk examination and visual inspection of histograms. Although the data were not normally distributed, independent t-tests were used to compare length of stay between returned and non-returned animals as they are robust for skewed data sets with big sample sizes57. Paired t-tests were used to compare length of stay at initial intake and post-return intake for returned dogs and cats. Nosotros then used Pearson's Chi-Square tests to compare intake historic period group, intake type, sex, and breed group (dogs simply) between returned and non-returned animals. Animals with render listed as their outset intake type between 2015 and 2019 were excluded from analyses for intake blazon (n = 14 dogs, n = 1 cats). Pearson's Chi-Square tests were used to compare return reasons, return frequency and outcome type by intake age group, sexual practice, and brood groups (dogs simply). If > 20% of cells had expected values below five, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test were used. Return reasons with n ≥ l were besides considered individually for dogs but. Mail-hoc analyses were conducted using standardized residuals58. For animals returned more than in one case, Fleiss' kappa was used to test the forcefulness of agreement betwixt the return reasons provided past the first and second returning owners. Binary logistic regression models were used to draw the likelihood of render (returned/not returned), return reason (owner-based/creature-based) and outcome (adopted/euthanized) based on intake age group, sexual practice, breed group (dogs just) and return frequency (outcome merely). Outcome was investigated among dogs only due to the small number of cats that were euthanized (due north = eighteen). Statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 without adjustment for multiple comparisons59, 60.

Data availability

The data governance arrangements for the study practice not permit us to redistribute Charleston Fauna Society data to other parties.

References

-

ASPCA. Shelter Intake and Give up - Pet Statistics. https://www.aspca.org/animal-homelessness/shelter-intake-and-surrender/pet-statistics. (2020).

-

Rowan, A. & Kartal, T. Dog population and dog sheltering trends in the The states of America. Animals 8, 68 (2018).

-

Mornement, K. M., Coleman, Grand. J., Toukhsati, S. R. & Bennett, P. C. Evaluation of the predictive validity of the Behavioural Cess for Re-homing K9'due south (BARK) protocol and owner satisfaction with adopted dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 167, 35–42 (2015).

-

Scott, S., Jong, E., McArthur, One thousand. & Hazel, S. J. Follow-upwardly surveys of people who have adopted dogs and cats from an Australian shelter. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 201, 40–45 (2018).

-

Neidhart, Fifty. & Boyd, R. Companion beast adoption study. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 5, 175–192 (2002).

-

Marston, Fifty. C., Bennett, P. C. & Coleman, G. J. Adopting shelter dogs: Owner experiences of the kickoff month post-adoption. Anthrozoös 18, 358–378 (2005).

-

Mondelli, F. et al. The bond that never developed: Adoption and relinquishment of dogs in a rescue shelter. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 7, 253–266 (2004).

-

Diesel, G., Pfeiffer, D. & Brodbelt, D. Factors affecting the success of rehoming dogs in the UK during 2005. Prev. Vet. Med. 84, 228–241 (2008).

-

Wells, D. L. & Hepper, P. G. Prevalence of behaviour problems reported by owners of dogs purchased from an animal rescue shelter. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 69, 55–65 (2000).

-

Kidd, A. H., Kidd, R. Grand. & George, C. C. Successful and unsuccessful pet adoptions. Psychol. Rep. 70, 547–561 (1992).

-

Patronek, G. J. & Crowe, A. Factors associated with loftier live release for dogs at a large, open up-admission, municipal shelter. Animals 8, 45 (2018).

-

Marston, 50. C., Bennett, P. C. & Coleman, G. J. What happens to shelter dogs? An analysis of data for one yr from three Australian shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. seven, 27–47 (2004).

-

Fricke, I. 'Render' is not a dirty discussion - Pets who come up back present opportunities for united states of america to learn, https://www.animalsheltering.org/blog/return-non-dingy-word (2017).

-

Hamrick, L. All in practiced time - Trial adoptions can pave the way to more and meliorate matches. https://www.animalsheltering.org/blog/all-practiced-time (2020).

-

Gunter, L. M., Feuerbacher, Due east. N., Gilchrist, R. J. & Wynne, C. D. Evaluating the effects of a temporary fostering program on shelter dog welfare. PeerJ 7, e6620 (2019).

-

Taylor, K. & Mills, D. The effect of the kennel environment on canine welfare: A critical review of experimental studies. Anim. Welf. 16, 435 (2007).

-

Shore, E. R. Returning a recently adopted companion animal: Adopters' reasons for and reactions to the failed adoption experience. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. eight, 187–198 (2005).

-

Hawes, S. M., Kerrigan, J. Grand., Hupe, T. & Morris, Grand. Northward. Factors informing the return of adopted dogs and cats to an beast shelter. Animals x, 1573 (2020).

-

Casey, R. A., Vandenbussche, South., Bradshaw, J. W. & Roberts, M. A. Reasons for relinquishment and return of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) to rescue shelters in the Britain. Anthrozoös 22, 347–358 (2009).

-

American Humane Association. Keeping pets (dogs and cats) in homes: A three-phase retentiveness study. (http://www.americanhumane.org/petsmart-keeping-pets-phase-ii.pdf, 2012).

-

Patronek, G. J., Glickman, L. T., Beck, A. M., McCabe, G. P. & Ecker, C. Gamble factors for relinquishment of dogs to an animal shelter. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 209, 572–581 (1996).

-

Patronek, G. J., Glickman, L. T. & Moyer, Grand. R. Population dynamics and the risk of euthanasia for dogs in an animal shelter. Anthrozoös 8, 31–43 (1995).

-

McGreevy, P. D. & Masters, A. M. Risk factors for separation-related distress and feed-related aggression in dogs: Additional findings from a survey of Australian dog owners. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 109, 320–328 (2008).

-

Martínez, Á. G., Pernas, G. S., Casalta, F. J. D., Rey, Thousand. L. S. & De la Cruz Palomino, 50. F. Run a risk factors associated with behavioral issues in dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 6, 225–231 (2011).

-

Dietz, L., Arnold, A.-M.Thou., Goerlich-Jansson, V. C. & Vinke, C. M. The importance of early life experiences for the evolution of behavioural disorders in domestic dogs. Behaviour 155, 83–114 (2018).

-

Kass, P. H., New, J. C. Jr., Scarlett, J. M. & Salman, M. D. Understanding beast companion surplus in the United States: Relinquishment of nonadoptables to animal shelters for euthanasia. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 4, 237–248 (2001).

-

Asher, Fifty., England, Grand. C., Sommerville, R. & Harvey, Northward. D. Teenage dogs? Evidence for boyish-stage conflict behaviour and an clan between attachment to humans and pubertal timing in the domestic dog. Biol. Lett. 16, 20200097 (2020).

-

Brown, W. P. & Stephan, V. L. The influence of degree of socialization and age on length of stay of shelter cats. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1–8 (2020).

-

Casey, R. A. & Bradshaw, J. W. South. The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 114, 196–205 (2008).

-

Buckland, E. L., Murray, J. K., Woodward, J. Fifty., Da Costa, R. E. O. & Casey, R. A. in ISAZ 2020.

-

Powell, L. et al. Expectations for domestic dog ownership: Perceived physical, mental and psychosocial health consequences among prospective adopters. PLoS ONE 13, e0200276 (2018).

-

Seksel, K. Preventing beliefs bug in puppies and kittens. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Pocket-size Anim. Pract. 38, 971–982 (2008).

-

Dinnage, J. D., Scarlett, J. Thousand. & Richards, J. R. Descriptive epidemiology of feline upper respiratory tract illness in an animal shelter. J. Feline Med. Surg. 11, 816–825 (2009).

-

Pedersen, N. C., Sato, R., Foley, J. E. & Poland, A. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus. J. Feline Med. Surg. 6, 83–88 (2004).

-

Hart, L. A. et al. Compatibility of cats with children in the family unit. Front. Vet. Sci. 5, 278 (2018).

-

Mehrkam, 50. R. & Wynne, C. D. Behavioral differences amidst breeds of domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris): Current status of the scientific discipline. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 155, 12–27 (2014).

-

Siettou, C., Fraser, I. Thousand. & Fraser, R. Due west. Investigating some of the factors that influence "consumer" pick when adopting a shelter dog in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 17, 136–147 (2014).

-

Weiss, Due east., Miller, K., Mohan-Gibbons, H. & Vela, C. Why did y'all cull this pet?: Adopters and pet selection preferences in five animate being shelters in the United States. Animals 2, 144–159 (2012).

-

Lepper, M., Kass, P. H. & Hart, 50. A. Prediction of adoption versus euthanasia amidst dogs and cats in a California animal shelter. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 5, 29–42 (2002).

-

Gunter, L. Grand., Barber, R. T. & Wynne, C. D. What'south in a name? Effect of brood perceptions and labeling on attractiveness, adoptions and length of stay for pit-bull-type dogs. PLoS One xi, e0146857 (2016).

-

Svoboda, H. & Hoffman, C. Investigating the role of glaze colour, age, sex, and breed on outcomes for dogs at 2 fauna shelters in the U.s.. Anim. Welf. 24, 497–506 (2015).

-

Voith, V. 50., Ingram, Due east., Mitsouras, K. & Irizarry, K. Comparing of adoption agency breed identification and DNA breed identification of dogs. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 12, 253–262 (2009).

-

Hoffman, C. L., Harrison, N., Wolff, L. & Westgarth, C. Is that canis familiaris a pit balderdash? A cross-country comparison of perceptions of shelter workers regarding breed identification. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 17, 322–339 (2014).

-

Olson, K. R. et al. Inconsistent identification of pit balderdash-type dogs by shelter staff. Vet. J. 206, 197–202 (2015).

-

Cohen, Northward. P., Chodorow, M. & Byosiere, Southward.-E. A label's a label, no matter the domestic dog: Evaluating the generalizability of the removal of breed labels from adoption cards. PLoS ONE 15, e0238176 (2020).

-

Duffy, D. L., Hsu, Y. & Serpell, J. A. Breed differences in canine aggression. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 114, 441–460 (2008).

-

Salonen, M. et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and breed differences in canine anxiety in 13,700 Finnish pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–xi (2020).

-

MacNeil-Allcock, A., Clarke, Due north., Ledger, R. & Fraser, D. Aggression, behaviour and animal care among pit bulls and other dogs adopted from an animal shelter. Anim. Welf. UFAW J. twenty, 463 (2011).

-

Kwan, J. Y. & Bain, M. J. Possessor attachment and problem behaviors related to relinquishment and training techniques of dogs. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 16, 168–183 (2013).

-

Duffy, D. L., Kruger, K. A. & Serpell, J. A. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment tool for dogs relinquished to shelters. Prev. Vet. Med. 117, 601–609 (2014).

-

Segurson, S. A., Serpell, J. A. & Hart, B. L. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment questionnaire for use in the label of behavioral bug of dogs relinquished to animal shelters. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227, 1755–1761 (2005).

-

Stephen, J. & Ledger, R. Relinquishing dog owners' power to predict behavioural bug in shelter dogs post adoption. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 107, 88–99 (2007).

-

Pirrone, F., Pierantoni, L., Mazzola, Due south. Chiliad., Vigo, D. & Albertini, M. Owner and animal factors predict the incidence of, and owner reaction toward, problematic behaviors in companion dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 10, 295–301 (2015).

-

Lord, M. Southward. et al. Owner perception of problem behaviours in dogs aged 6 and 9-months. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 232, 105147 (2020).

-

American Kennel Club. List Of Breeds By Group. https://www.akc.org/public-educational activity/resources/general-tips-information/dog-breeds-sorted-groups/ (2020).

-

Protopopova, A., Gilmour, A. J., Weiss, R. H., Shen, J. Y. & Wynne, C. D. L. The effects of social training and other factors on adoption success of shelter dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 142, 61–68 (2012).

-

Fagerland, Thousand. W. t-tests, non-parametric tests, and large studies—a paradox of statistical practice?. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12, 78 (2012).

-

Sharpe, D. Chi-foursquare test is statistically pregnant: At present what?. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 20, 8 (2015).

-

Feise, R. J. Practice multiple outcome measures crave p-value adjustment?. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2, 1–four (2002).

-

Rothman, M. J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology, 43–46 (1990).

Acknowledgements

Nosotros thank Charleston Animal Society for providing their support, expertise, and data throughout this written report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P., C. R., B. W. and J.S. conceived and designed the study. D.S. and M.M. provided the original data. L.P. extracted the data, performed the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.S. and 1000.M. are paid employees of Charleston Animal Guild. Charleston Animal Society did not fund this research or contribute to the study pattern, data analysis or initial drafting of the manuscript. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'south annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as you give advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other tertiary party cloth in this article are included in the article's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the commodity'south Creative Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this commodity

Powell, L., Reinhard, C., Satriale, D. et al. Characterizing unsuccessful animal adoptions: historic period and breed predict the likelihood of return, reasons for return and post-return outcomes. Sci Rep 11, 8018 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87649-two

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87649-two

Farther reading

-

The bear on of returning a pet to the shelter on future animal adoptions

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a annotate y'all agree to bide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you lot find something calumniating or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-87649-2

Posted by: goodwinhatiou.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Can We Get More Animals Adopted"

Post a Comment