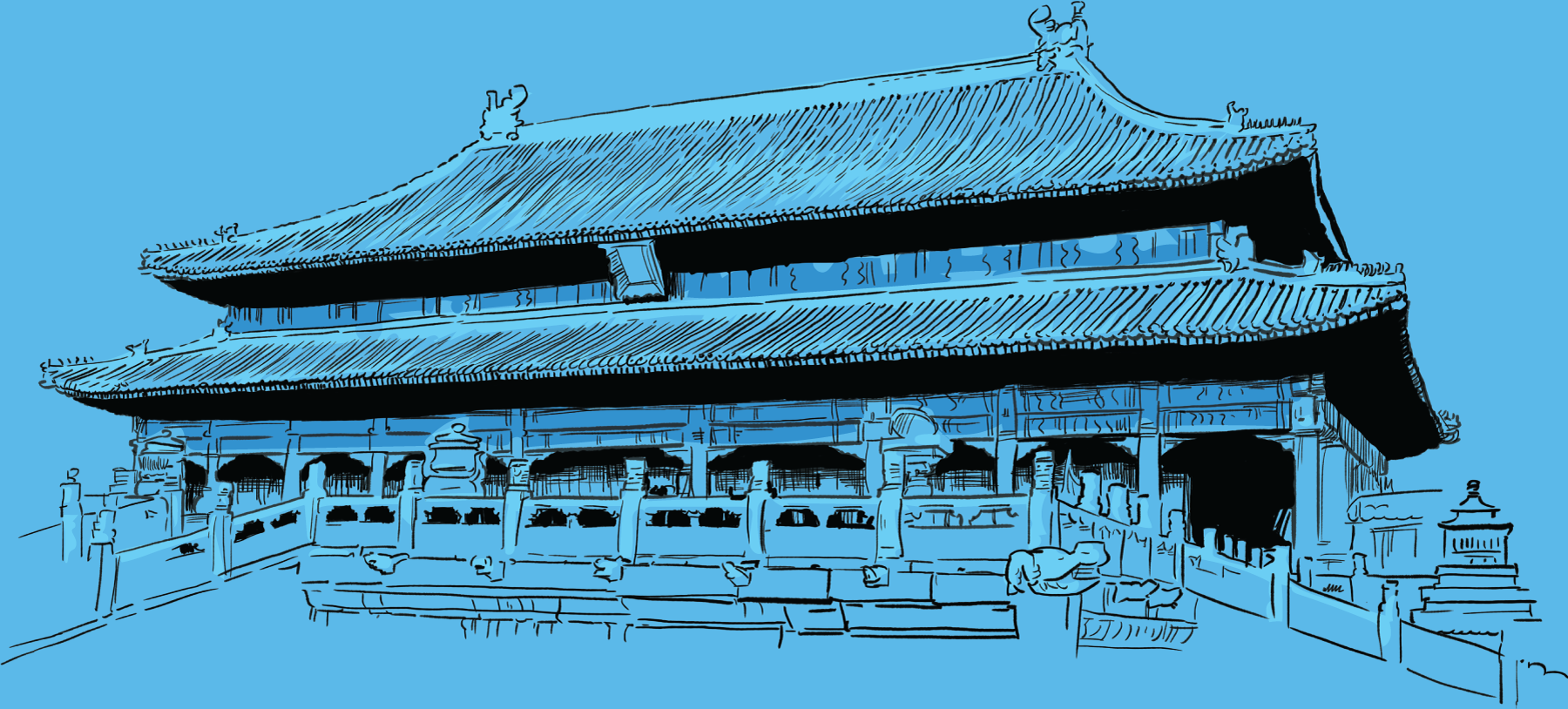

What Was The Subject Of Painting Does In The Garden Palace In The Forbidden City

Life inside the Forbidden City

chapter 3

In the Forbidden City, being the emperor didn't equate to a life of limitless power or pleasure

AUGUST 08, 2018

Marcelo

Duhalde

For the emperor, life in the Forbidden City was not as opulent as one might imagine. While each dynasty claimed the emperor was heaven's earthly representative destined to drive the immense country forward, the emperor remained a link in a giant bureaucratic chain compelled to follow rigorous protocols dictated by tradition.

He was obliged to attend meetings on matters of public interest from the early hours to rule on appropriate punishments and executions. He would also receive a steady stream of delegates to discuss policies and sign edicts. To compound his daily pressures, the emperor's routine was supervised by eunuchs and officials who did not always have his best interests at heart.

Daily duties

-

The emperor had to rise at 4am. This early rising was called ch'ing chia, meaning, "Your appearance is begged in court". The emperor used a palanquin (four guards at the front and several eunuchs to the rear) to reach the hall where he was needed for the daily audience with his courtiers. He then returned to his chamber to snatch a little more sleep.

-

The emperor formally took breakfast at 7am in spring and winter, and 6am in summer and autumn. He would pick name cards of the officials from a plate prepared by the eunuchs. After breakfast, he opened and read the memorial presented by ministers and other officials.

-

There was a second audience at midday when the emperor's main duties were to read and write comments on local government memorials, or reports. More than a hundred memorials came every day from all over the empire.

-

Lunch time was followed by relaxation, when the emperor might unwind by composing poems or enjoying the garden.

-

More memorials. The papers were returned through the directorate of ceremonial office to the country administrative divisions after the emperor signed them off in red ink.

-

Light supper and snacks. At this time the emperor's duties were complete and he could retire to his chambers.

"No one in any dynasty of China ever lived a more rigidly controlled court life than the emperor of the Ch'ing. Due to strict observance of traditional conventions of the court, the freedom of the emperor was far less than that of an ordinary man."

"As long as the emperor stayed within the court, he was restricted in every way by tradition. Consequently, it was only natural that the emperor wished to stay away from court as much as possible. When the emperor lived in a detached palace, he could lead a comparatively free life, for he was exempted from the early-morning audience, he could dine with his consorts, and every manner and custom was simplified. Nevertheless, he was not as free as an ordinary person, for he still had to give daily audiences and promulgate instructions considering the documents submitted to him … The only amusements the emperor could enjoy in the court were to attend a stage show, to practice calligraphy, and to paint. No other amusements were permitted."

–Su Chung (the name given to Japanese-American Yokiko Toshima, when she married a man whose family had close ties to Emperor Puyi) from her book Court Dishes of China, first published in 1965.

STATE AFFAIRS

Each emperor conducted the state religious rites deemed necessary to maintain the harmonious balance between heaven and the nation.

Most of the administrative institutions of the Qing Dynasty were inherited from the Ming period. The Qing emperors were autocrats who made their decisions prevail in matters of government and state affairs. Institutions such as the grand council, grand secretariat and political conference only had assisting duties, and were not allowed to take high-level decisions themselves.

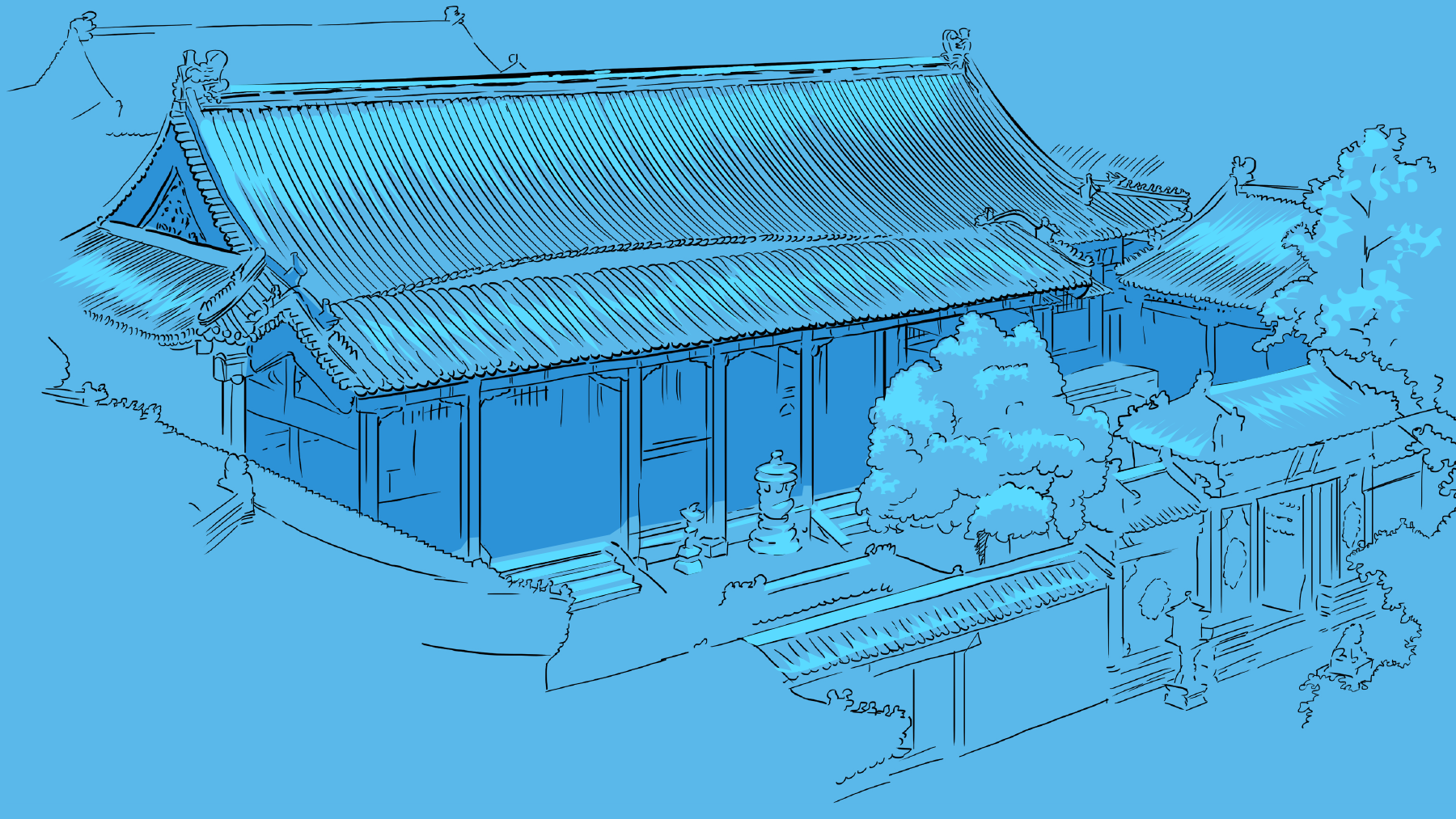

PLACES

The Ming dynasty established the Palace of Heavenly Purity as the residence of the emperor, a tradition followed by Qing emperors. When the Yongzheng Emperor (reign 1722-1735) moved his home to the Hall of Mental Cultivation, he continued to hold court in the Palace of Heavenly Purity.

PALACE OF HEAVENLY PURITY

Built in 1420 and rebuilt in 1798 to repair fire damage, the emperor read, and signed documents, interviewed ministers and envoys in the Palace of Heavenly Purity. Banquets and other ceremonies would occasionally be held here too.

-

A plaque engraved with four Chinese characters written by Emperor Yongzheng meaning "justice and brightness" hangs on the throne

-

The box with the edict for the succession was placed behind a board closely related to the Qing system of designating the successor to the throne in secret.

-

Two pairs of verses written by the Qing emperors adorn the columns

-

Red candles and a large mirror next to the throne ward off evil spirits

-

The throne is arranged on a platform

-

Incense burners surround the throne

-

Behind the throne is a gilded wooden panel etched with dragons playing with a pearl

The emperors after Yongzheng followed the practice of keeping the imperial successor a secret. The emperor wrote a secret edict naming a successor from his sons. Two copies were made. One was kept by the emperor, the other was sealed in a box at the back of a horizontal board hanging over the throne.

After the emperor's death, the regent ministers opened the two copies of the secret edict to verify with other courtiers the designated prince to succeed to the throne.

THE HALL OF MENTAL CULTIVATION

After the reign of Yongzheng the emperors used this hall for routine administrative affairs. It was divided into a front and rear section, connected by a hallway. The five-chamber rear section held the emperor's living quarters while the front was used for administrative affairs. The emperor granted interviews to his officials in the central room where the throne was situated. The western Warm Chamber was where he frequently read memorials and discussed political affairs with his ministers.

All the palaces in the inner court were designed following the rules of strict symmetry

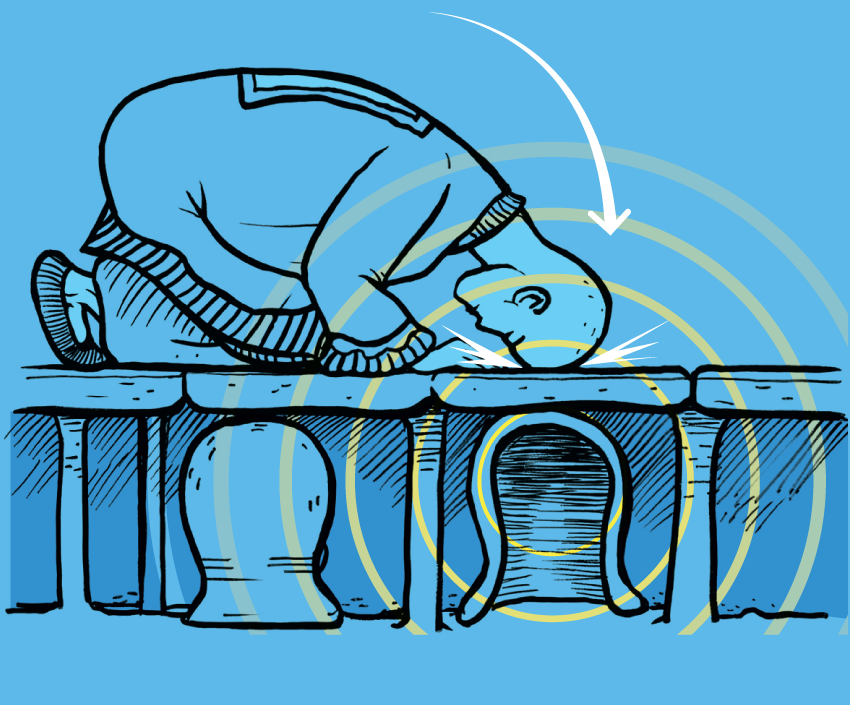

KNOCKING THE TILES

Inverted mud jars were placed under the floor tiles of the Hall to create a special resonance or echo when certain tiles were struck. Ministers who were given the honour of an audience with the emperor were to mention their ancestors while kowtowing. When striking their foreheads against the floor the more resonant sounds were considered a sign of great respect for the emperor. It became common practice for eunuchs in charge of the hall to indicate which places had the best resonance in exchange for a bribe. Guests found it extremely difficult to produce a noteable sound however hard they slammed their heads against the floor tiles without having first greased someone's palm.

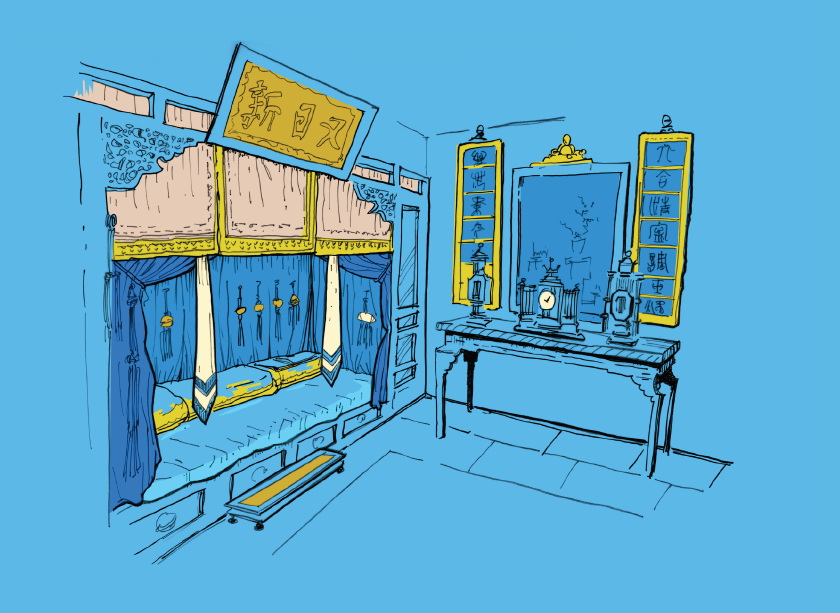

BED CHAMBER

The emperor's bed was at the eastern end of the Warm Chamber.

-

The wooden platform-bed (3.5 m long), was hung with a gauze curtain in summer and a lined silk-satin curtain in winter.

-

Decorated with pennants, the interior curtain was hung with ornamental perfume sachets.

-

The chamber was warm in winter and cool in the summer. The floor was covered with woollen carpets and an underfloor heating system was fuelled by an outside wood fire. Charcoal burners were also used inside the room.

Feeding his majesty

Another common misconception is that the emperor routinely feasted on lavish meals. His diet was balanced, but surprisingly plain. Both the Ming and Qing dynasties ate in accordance with the same principle: a diet must promote health.

The scale of infrastructure needed to provide food was immense. The imperial kitchen was composed of three parts: the main kitchen, tea kitchen and bakery. Each had a chef and five cooks, a supervisor and an accountant who procured and tracked supplies.

Menus always carried the cook's name so that dishes could be easily reordered – and culprits could be identified if anything suspicious happened. Imperial recipes were essentially sophisticated versions of meals traditionally enjoyed by the common people.

SERVING MEALS AND PALACE CUSTOMS

Qing emperors made it their custom to eat meals alone except during special ceremonies, without even the pleasure of family for company. Although the Qianlong Emperor sometimes invited a consort to dinner, protocol dictated that all persons, except a dowager empress, had to stand in the emperor's presence.The empress and imperial concubines took their meals in their own palaces. The emperor's diet mostly consisted of pork, mutton and game, fowl and vegetables. All the dishes were served with covers that were removed when the emperor took his seat at the table.

Menus were drawn up in advance for each meal and submitted to the inner court minister for approval. Every menu was archived.

THE TABLE SET

included enamel bowls, plates and dishes, blue and white jade sunflower tureens and gold and silver thread embroidered napkins

Beef was banned in the palace because it was considered a sin to consume animals that were beasts of burden.

Qing Dynasty emperors had two formal meals a day. These were served on gold dishes or special porcelain manufactured in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province. During the Qing Dynasty, emperors did not have a fixed place or time to take their meals. The emperor would inform his guards when he wished the meal to be served and would sit down to eat wherever he happened to be at that time of day.The kitchen officials ordered eunuchs to set whichever table was in the emperor's vicinity the moment they were informed of the mealtime.

THE IMPERIAL KITCHEN

Located west of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the imperial kitchen had a director, deputy and assistant directors, manager, executive manager, and clerks to handle the emperor's daily meals. In total, more than 200 officials, cooks and eunuchs were employed. The emperor's meals were prepared separately from everybody else's meals. The Director of the Eastern Depot cooked the meals during even months, with the Director of Ceremonial taking over during odd months.

POISON FEAR

HEALTHY HABITS

The Imperial kitchen adjusted the diet of the emperor according to the season. Lighter dishes were served in the summer with heavier, more nutritious meals in winter. It was believed that light food increased body fluids, while heavier meals created more vital energy.

On June 8, 1789, Qianlong took his breakfast in the Yihong Hall (Hall of Partial Rainbow) at a lacquer table. He was served:

On December 13, the emperor took his late meal in the eastern room of the Yangxin Hall. His meal included:

SOURCES OF FOOD SUPPLIES

All ingredients were supplied by the Palace Food Directorate and imperial kitchen. These agencies had a system for uninterrupted food supply, much of which came in the form of tributes from distant regions. More than a hundred eunuchs worked farms to supply lamb, geese, chickens and ducks, as well as running the wine office, which produced fermented soy wine. They also operated the imperial mill and vegetable garden. Fresh plums, loquats, bamboo shoots, tea, cassias, cherries preserved in honey, and fragrant rice were the main products delivered by refrigerated barges along the Grand Canal costing over 30,000 taels (US$375,000) a year.

The Qianlong Emperor usually took his tea with milk. Herds of cattle were maintained, with 100 cows kept in reserve to provide milk for the emperor. Spring water from Yuquan Shan was used for cooking and to make tea.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT SPECIALTIES

SENT TO THE PALACE

MEDICINAL FOOD

Qing Dynasty emperors ate food with medicinal properties. Many records from the Qing Palace archives still exist which mention the use of wines, juices, extracts, preserved fruits, and sugar as health-giving items.These foods were believed to stimulate the stomach, kidneys, and appetite; reduce internal heat; reduce phlegm; nourish the body; and prolong life.

According to the Qing dynasty statutes, Emperor Guangxu (reign 1875-1908) had an infirmary staff of 13 imperial physicians, 26 officials, 20 assistants and 30 doctors.

Dress codes

Garments have always reflected a culture's social and historical evolution. Ancient Chinese rulers imposed strict codes in each era, which were usually linked to their ethnic traditions and identity. Each dynasty had stipulations for the material, colour, decorative patterns and style of dress that distinguished royal, civil and military officials from commoners. Anyone defying the dress code was severely punished. The Ming rulers (1368-1644), for example, forbade anyone to wear the Mongol attire of the previous dynasty. The Qing dynasty (1644-1911) imposed substantial changes in dress to reflect their Manchurian origins, which were met with strong resistance from the Han people

MING DYNASTY (1368-1644)

The attire during this period reflects the loose fitting and elaborate style of the ancient ethnic Han people. Buttons became popular during the Ming dynasty, along with circular collars. Jackets became longer. Light colours were popular in the early era, with the front of garments decorated with accessories made from gold, jade and pearls. Men's clothes adopted a form of chador and circular collar. Garments featured broad sleeves, inlaid black brims and cyan circular collars. Most were made of silk. Ming was the last dynasty in which men wore a skirt.

During this period, clothing for men and women became more voluminous: long robes with wide sleeves for men and a shorter robe worn over a wide skirt for women. For much of its three centuries, the Ming period featured great prosperity and the production of all manner of goods expanded.

CIVIL AND MILITAR FEATURES

Symbols of rank and office were mandatory in China since the Tang Dynasty, when the first, and only, female emperor of China, Emperor Wu Zetian, ordered all officials to wear embroidered gowns; birds were embroidered on the gowns of civil officials while military officials donned gowns decorated with beasts. The Ming dynasty continued the tradition, distinguishing types and ranks of officials with buzi – embroidered cloth – attached to the chest and back of gowns.

The Buzi (ornamental patches)

These striking-looking ornamental patches depicted all manner of real and mythical beasts. Of all the features on the uniforms of Chinese officials, the buzi most eloquently expresses the relationship between clothing and power. Cranes, golden pheasants, peacocks, wild geese, silver pheasants, egrets, larks and quails were used, as were exotic mythical birds that resembled a cross between an egret and a peacock on the civil officials buzis. The crane is a symbol of longevity because it has a long lifespan, with its white feathers standing for old age. The buzi used on military officials' clothing depicted tigers, lions and panthers, as well as beasts from the outer reaches of an artist's imagination. Animals were used to signify different ranks – nine ranks for civil and nine for military officials.

Civil officials samples

QING DYNASTY (1644-1911)

Clothing also played a relevant part in the life of the Qing emperors. Dress code in the palace signalled political hierarchies. One of the purposes of these rules was to observe ancestral Manchu traditions.During the Chong De period (1636-1643) the dress code was considered to be of fundamental importance to the stability of the country. Abahai (Qing Emperor Hong Taiji, reign 1626-1636), placed so much importance on equestrian prowess that he considered horsemanship and archery "two basic skills" of China. Riders and archers wore tighter-fitting suits.

Share this story

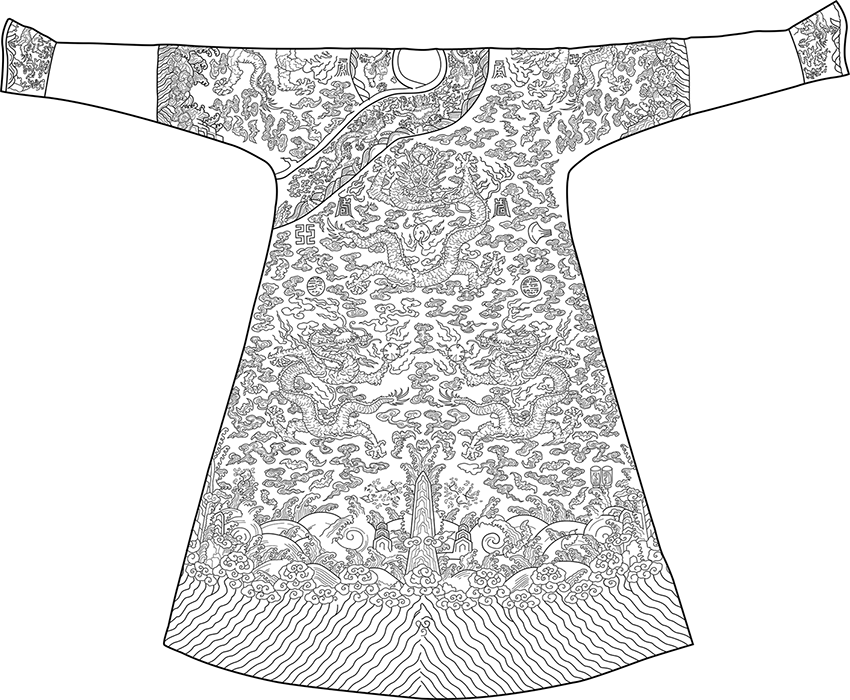

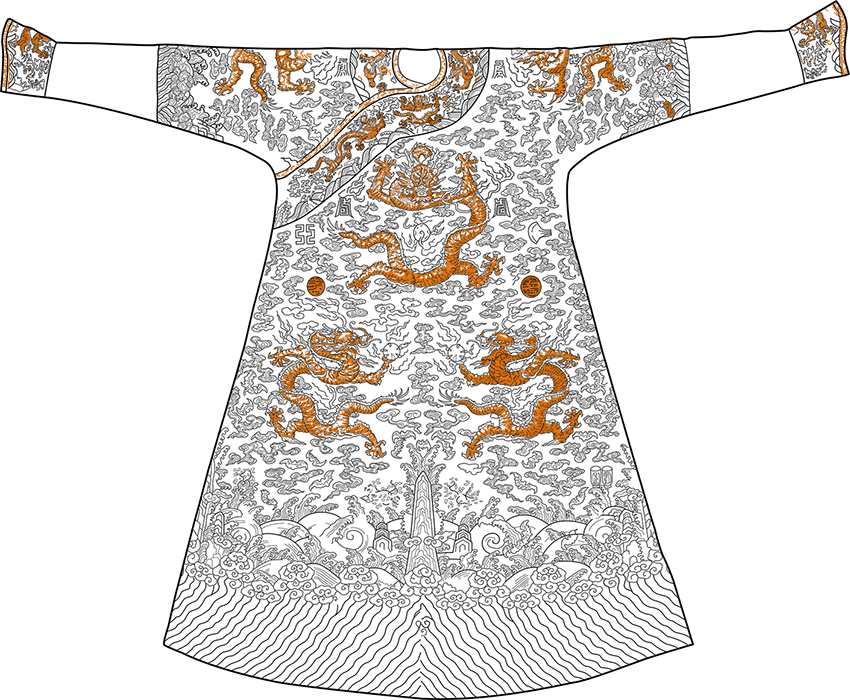

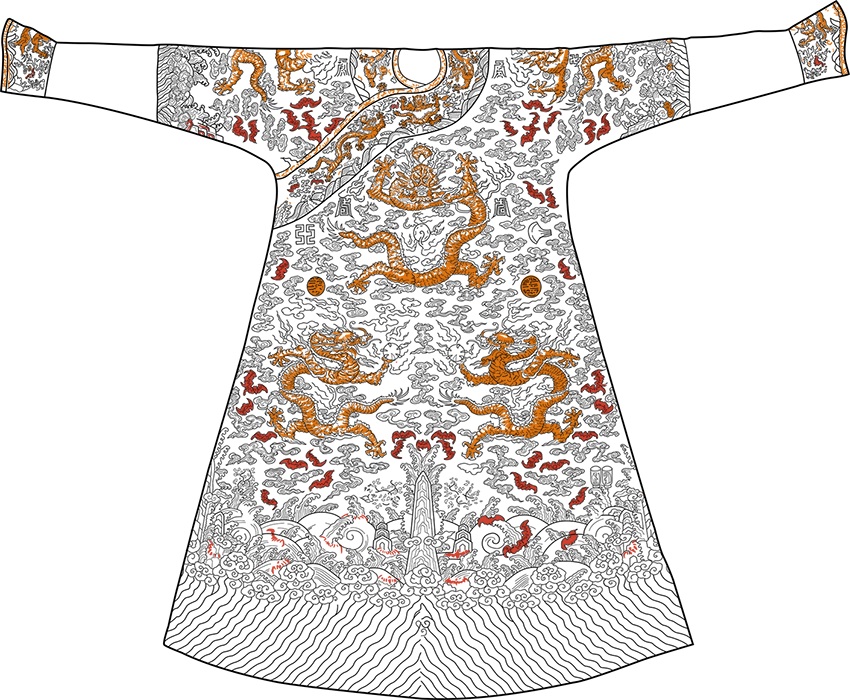

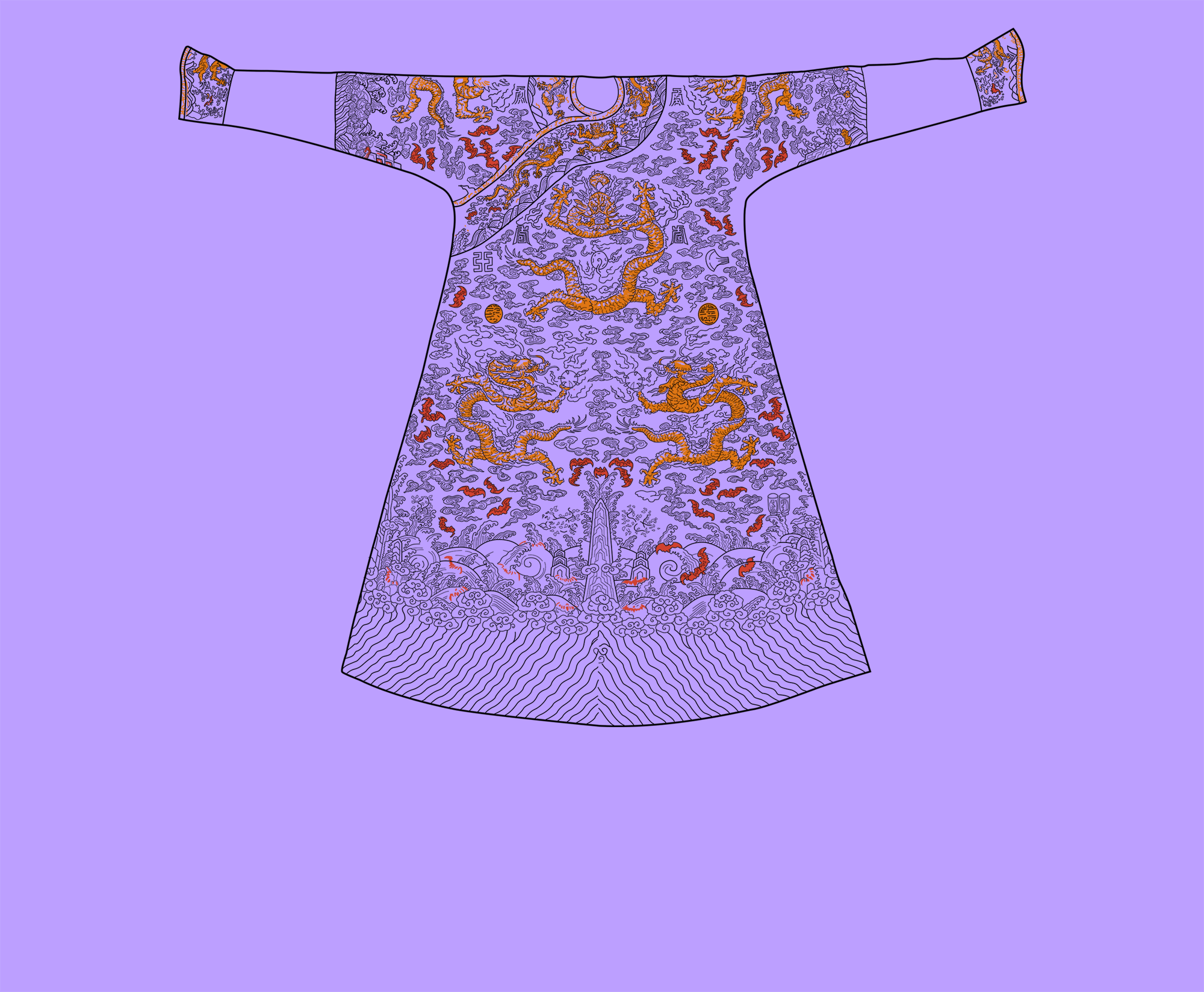

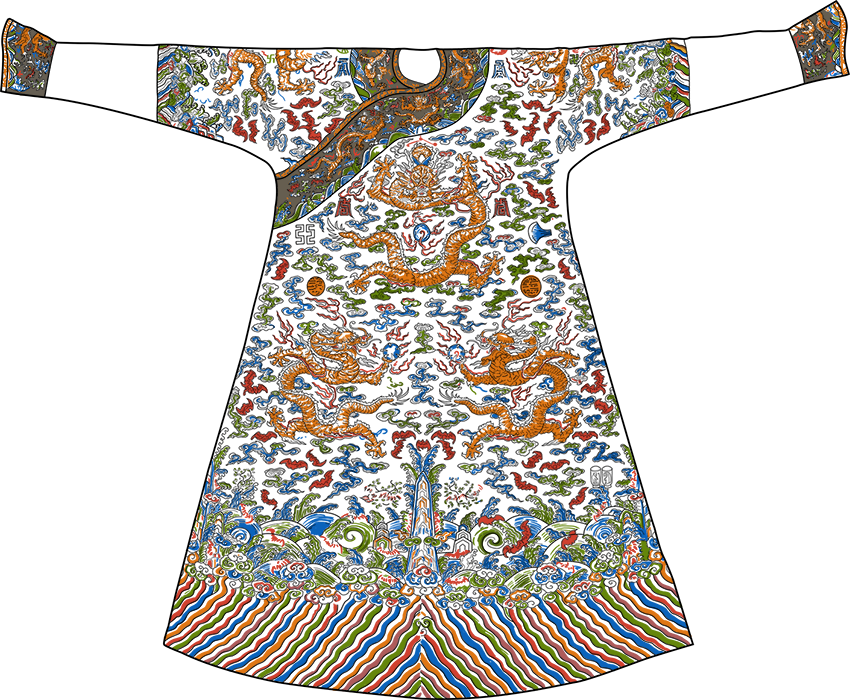

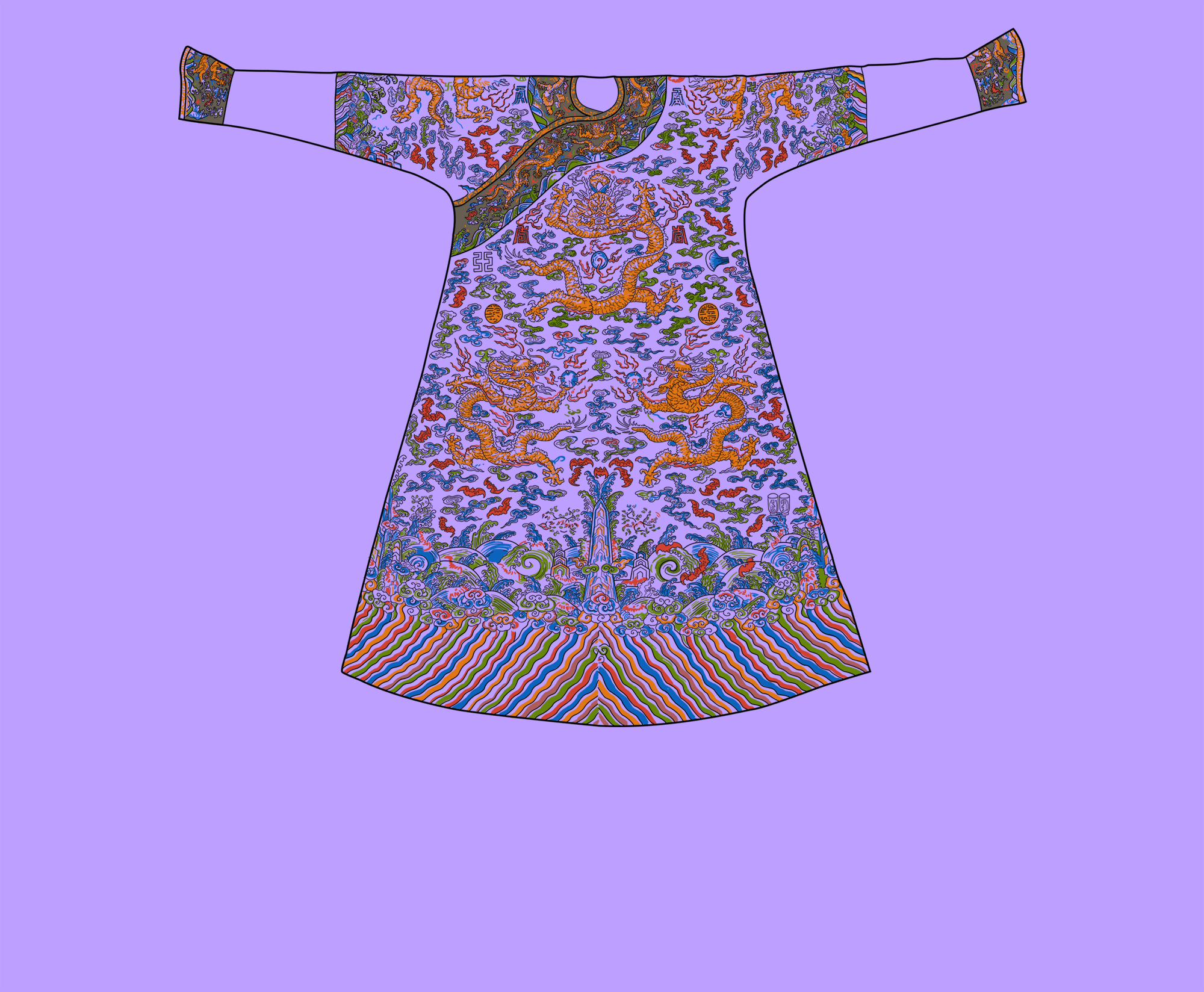

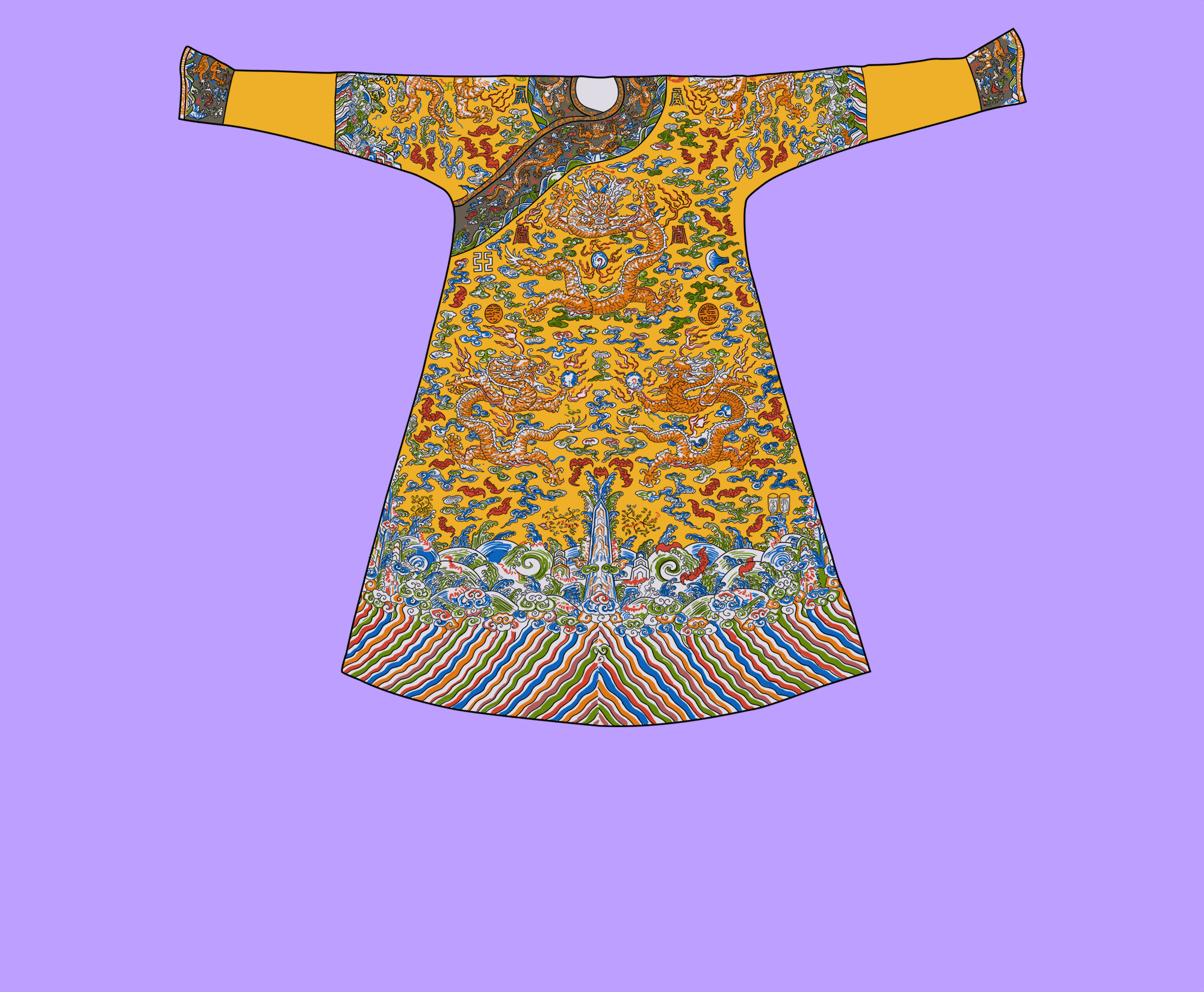

THE DRAGON ROBE

The emperor's most remarkable attire, in terms of ornamentation and symbolism was the Dragon robe – an auspicious garment reserved for festive occasions.

The dragon robe was not simply a means for the emperor to appear powerful: it was also meant to bring good luck to the people. An old Chinese proverb says that the reign of every emperor starts when he dons his new robes. The imperial robes of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) lent legitimacy to this proverb.

It required two and a half years for court tailors to make it. A palace shop was reserved for tailoring the emperor's clothes. The patterns and cuts were developed subject to approval from the emperor and the highest ranking officials.

The patterns were then passed on to the silk manufacturers. When the fabric was ready, it was cut by an artisan before the tailor received it and began the embroidery. Only the finest threads were used for the embroidery, with some made from gold. Five hundred artisans contributed to the stitching and another 40 were required for the gold embroidery.

The robe is tight fitting with sleeves tapering into flared cuffs that resemble the hoofs of a horse – a reference to the Manchu equestrian background.

A dragon is the dominant motif, with four dragons surrounding the neck symbolising the main directions of the universe, and four on the front and back of the skirt indicating the midway directions of the universe.

Another motif applied to the emperor's robes was a red bat, the symbol of happiness. The Chinese word for bat sounds identical to the word for good fortune

The robe included a series of symbols, such as large dragons on the chest and back and small dragons on the shoulders and skirt. Apart from auspicious symbols, the dress featured mountains and waves.

The colour at the bottom of the robe indicated rank and lineage, with yellow restricted to the emperor.

A SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM OF THE UNIVERSE

"The lower border of diagonal bands and rounded billows represent water. At the four axes of the coat, the cardinal points: rise prism shaped rocks symbolizing the earth mountain. Above is the cloud-filled firmament against with dragons, (symbol of imperial authority) coil and twist. The symbolism is complete only when the coat is worn, the human body becomes the world axis, the neck opening, the gate of heaven or apex of the universe, separates the material world of the coat from the realm of the spiritual represented by the wearer's head"

– John E Vollmer, curator and scholar of Asian art, textiles, costumes and design. He is the author of 30 museum exhibition catalogs and multiple books and articles.

FURTHER READING

This is the third chapter exploring the life in the Palace Museum

We would like to invite readers to navigate between the chapters as they are published. Other visual narratives will investigate daily life in the palace and follow the odyssey undergone by the royal collection. We hope you enjoy immersing yourself in the project much as we did making it for you

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

ABOUT THIS GRAPHIC

Here are some of the awards that this graphic has obtained

-

Gold medal

Wan-Ifra Digital Asian Media Awards

2019 Edition -

Bronze Medal

Society For News Design

Edition 40

Follow our graphics team

-

@SCMPgraphics

-

SCMP infographics

-

SCMP infographics

Enjoying South China Morning Post graphics?

Here are some other digital native projects you might want to visit

Hi, Internet Explorer user!

This site has some features that may not be compatlibe with your browser. Should you wish to view content, switch browsers to either Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox to get an awesome experience

What Was The Subject Of Painting Does In The Garden Palace In The Forbidden City

Source: https://multimedia.scmp.com/culture/article/2158740/forbidden-city/life/chapter_03.html

Posted by: goodwinhatiou.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The Subject Of Painting Does In The Garden Palace In The Forbidden City"

Post a Comment